29th January 2020

Until 1998 I had hardly ever sailed before and never in a sail boat with a cabin.

By the end of 2015 I had clocked just over 12,000 nautical miles since 1998 when, at 42, I had bought my first cruising boat. When I retired in 2013 I was on my fourth sailing boat, a Sadler 32.

I’d spent in total a little over the equivalent of a year at sea. Not too bad for someone running a business and starting so late. Week end sailing allowed plenty of practice for tidal calculations, departures and arrivals within the Thames Estuary’s numerous river bars, creeks and swatchways. I had also crossed the North Sea at least once, every year.

But in the last four years up to the end of the 2019 season I’ve sailed a further 18,000 miles and I’ve now spent more than three years of the last 21 years at sea. I’ve sailed further than most but not nearly as far as some.

There was always a plan to sail further. I’m smitten by the sea and I’ve always devoured books and articles on sailing, from the great masters of the past, to the current heroes of today. I’ve also had some very wise close friends who are hugely experienced in the ways of the sea.

I always imagined that my first longer voyage would be crossing an ocean. Perhaps a North Atlantic circuit, but various things got in the way.

I’m a single-handed sailor, for one very good reason at least, as my wife does not enjoy being on the water. Sally wants me to do what I need to do in my sailing life, so keeps the home afloat while I’m away and never ever expects me back until ‘Talisker 1’ and I return home to the Thames Estuary.

Sally is not the only reason I sail by myself. I’ve always preferred sailing alone.

The other reason for not going too far was that I decided I did not want to leave my boat and fly home at the end of a cruise. The very idea of leaving my boat in some far flung place appalled me … and anyway, I love sailing in home waters when I do get home.

So that put paid to any notion of an ocean crossing until my great friend James Robinson and I joined Australians, Kris and David, on their Kaufman 49 ‘Taipan’ for their cruise from the Canaries to the Caribbean in March 2019. Much as I enjoyed their company, I would have preferred to have sailed the voyage alone on my own boat.

Master Mariner James Robinson mid Atlantic 2019

James Robinson … the Carribean after our Atlantic crossing 2019

Martinique … Safe Arrivals after our Atlantic crossing

To regress a little, I was in luck in 2007 when I took a practical sailing exam and needed crew on my own boat to demonstrate my incompetence to the examiner. My great friend, the aforementioned and incomparable James Robinson, brought along David ‘Doc’ Foreman. I’d first met James, who was already a mentor to me, when he taught me in 1998.

Doc is also a single-hander who has sailed to the Arctic and to South America and back and wrote a very good book. A must read for anyone contemplating sailing in the ocean.

Doc prides himself on sailing professionally. I now share his desire to complete unremarkable cruises. An unremarkable cruise will mean it’s been a safe passage. I also strive for a smidgeon of his professionalism and try not to have adventures! Adventures mostly happen when one makes mistakes!

Over the years I’ve ruthlessly exploited Doc’s knowledge and the small amount of his wisdom that I’ve gained has been golden.

Doc and Rival 41 ‘Tuesday of Ore’ in 2019

James Robinson at the helm of ‘Endeavor’ in the River Thames 2018

Me & James Robinson St Katherines Dock in early 2018

In 2014 my preparation to sail further started in earnest. I decided that my Sadler 32 ‘Samingo ll’, although capable, was not going to take me in to the ocean. I wanted something a bit bigger and all my thoughts were on heavier and steadier. James and Doc gave me their opinion when I was considering the best Rival ever built, the 38.

They knew more about my style of sailing than I did. “How about a Westerly Typhoon?”

Only 40 were built. I saw about five of them before settling on the 20th Typhoon Westerly produced. Built in 1991, TN20 is called ‘Talisker 1’.

By 2016 I’d had two years of local sailing with ‘Talisker 1’ making many upgrades and improvements in readiness for a long off shore voyage. Some of the work was bespoke. Only the mast remained of the original rig and I added a permanent inner forestay to fly a heavy weather staysail.

Southern North Sea late 2017 after my second voyage to Norway. A single reef in the main and flying the stay sail

In hindsight, this was a masterstroke. With a double reefed main and staysail she is very powerful indeed and eats the miles on the beam or to windward in heavy weather and gets stopped by nothing.

‘Talisker 1’ also sails well in light airs and can be reefed right down in a blow. Rob Kemp, who designed and manufactured the sails, put in a deeper 3rd reef in the main together with a slightly heavier cloth for that area of sail. The sails were also built to a tough ocean specification.

Triple reefed main in the Atlantic 2018

The sail plan was simple and very easy to use.

The new boom was single line reefing for reefs 1 and 2 and double line for reef 3. All lines led back to the cockpit.

A gantry was built to house solar panels and various instruments. The battery bank was upgraded.

March 2015. Tim and Ed from Mr Stainless, Suffolk YH, fitting the gantry

Ready for Solar Panels

Solar Panels

Raymarine’s state of the art Evolution self-steering with Linear Drive had also been installed. I discussed steering with Harry Heasman at Raymarine. Harry told me that, provided I generated power, the steering would take me, like many other boats fitted with the same system, round the world.

There is a limit to what one can afford. The expensive wind vane steering that I coveted, and frankly would still love to have, would have to go on the back burner. Instead and ingeniously, the old ST6,000 steering system was plumbed, in such a way, that if I had to swap, I would just have to replace the drive unit, flick a switch and I’d be on the old autopilot. However, replacing the hydraulic arm in a seaway would be a challenge. Although I have practised in flat water, thankfully I’ve never had to do it in anger.

Doc and James had been in my ear relentlessly. If you want to sail in the ocean alone you have to first do some increasingly longer cruises. They suggested sailing to Norway via Scotland. It’s about 260 nautical miles coast to coast and it’s also ocean conditions. Both Doc and James were adamant this should be done.

I’ve read and heard so many stories of people running into problems a long way from home. It’s a mystery that people who have not done much sailing alone, and some of them hugely competent offshore sailors and much, much better sailors than I will ever be, set off in to the ocean without understanding what is required of a solo sailor. Thanks to Doc and James I went off and rehearsed a few ‘longer short’ passages properly, if only to confirm what I probably already knew. I had been listening to Doc for years talking to me about the disciplines of long distance solo sailing, which differ from sailing with a crew.

I had of course sailed solo the coastal and Southern North Sea, but work commitments had not allowed me to exceed a passage of more than 100 nautical miles alone. I had tested myself in a gale six hours from Oostende. I had also been cold and terribly seasick forty miles from land. I would be seasick again but I vowed never ever to feel cold again.

As if to test the cold theory I sailed across the North Sea on one of the coldest nights this century. The sails and sheets were crisp with ice and the deck a dangerous skating rink. After a long beat across the North Sea I arrived safely in Suffolk Yacht Harbour on the River Orwell and fell into a deep sleep. I woke the following morning to find a foot of snow on the deck. The cabin was as warm as an igloo. I’d also not been cold on the passage. Success!

I had sailed much longer distances, prior to my Atlantic cruise in 2018, but always as a crew member. I had an inkling of what to expect from the ocean although nothing will really prepare you for that vast wilderness if you’ve not been out there.

So taking the advice of Doc and James the final tests for my ship and me were in 2016 and 2017 when I sailed from the Thames Estuary to Norway via Shetland. In 2016 I returned home via the Kattegat and the Kiel Canal. In 2017 I returned to Peterhead from Stavanger, my longest single-handed passage to date, of 54 hours. I now knew for certain I could sail in the ocean. The lessons learned in those higher latitudes, not to mention the start of my love affair with Orkney, Shetland and Norway were very important.

Fair Isle 2017 a magical experience

‘Talisker 1’ & ‘Endeavor’ North Haven, Fair Isle 2017

On passage to Bergen, Norway from Shetland in 2017. A testing sail!

Photos always flatten the sea. The coast of Norway finally approaches 2017

My whole sailing life in cruising boats had been a preparation to sail in the ocean. By the time I sailed down Channel in June 2018 heading for the Atlantic I had thoroughly tested all the systems on my boat. Although anxious about myself, by now I knew I’d rehearsed my part fully too. I had also bonded with my ship. She was as comfortable as an old pair of loafers!

Two crucial lessons had been learnt. The first was the utter irrelevance of when arrival will be. The other was to really take one’s time and prepare properly for departure and arrival. This should be the case however far or short a cruise has been. Perhaps a caffeine fix 30 minutes before arrival if slightly tired. You have not arrived until you’re securely anchored or moored in a safe place. I would start preparing for arrival on longer voyages when still 24 hours away. I also preferred to arrive in daylight in unknown places and was quite happy to bide my time with plenty of sea room.

The exception to make haste to arrive was beautifully described by round the world cruising couple John and Kara Pennington in their splendid book ‘Orca’, featured by Tom Cunliffe in the September 2018 issue of Yachting World. John writes how they had to make the best possible time to seek shelter in an unknown estuary on the east coast of Africa as a terrible life threatening storm approached.

Kara, Dean & John on the roof terrace of the Royal Norfolk and Suffolk YC with ‘Sentijn’ dead centre in the background in 2018

I did take enormous pleasure with my arrival in Porto Santo, Madeira. It was overcast as I neared the island so did not see it until about 20 miles away. I was astonished to be there. I could not believe I’d sailed so far. For so long Doc had told me about his arrival in Porto Santo and there was me … sailing in to the lee of the island and the bay of Porto Santo itself. It was a magical moment!

Porto Santo. After 5 days and 800 nautical miles from Cedeira, NW Spain

Rounding the south east end of the island of Porto Santo. A magical moment

‘Talisker 1’ Porto Santo

Obligatory wall art Porto Santo

The bay of Porto Santo

One of the best bits of advice given to me by Doc was to pretend to be ten years older and to move around the boat like an older person. An accident to the crew will disable the ship.

Only once did I momentarily stop behaving old on my Atlantic cruise in 2018. I’d let go with both hands down below and a sudden movement had me thrown across the cabin. Luckily, nothing got broken. It was a reminder to move slowly and like the mountain climber, always having three parts firmly planted.

I’ve always been surprised by articles about MOB exercises. Invariably, photographs show recoveries in relatively easy conditions. But if one of you goes MOB sailing downwind at night with 30 knots of wind up the chuff then the chances of recovery are pretty thin to non-existent. More thought should be given to staying on board!

For the solo sailor, an MOB would be curtains. It’s so easy not to clip on in a flat sea just to make an adjustment of some sort on the deck. I endeavour to be relentlessly disciplined and I keep my life-harness lines short.

I’ve already written that an injured crew disables the ship but by far the most important thing is getting enough rest. Fatigue can kill you.

My simple rule for sleep is to lie down at every opportunity, night and day, and set the alarm clock for 20 minutes. If I’m not working the boat, drinking, eating or enjoying the view I’m straight in to my pilot berth with a book. I like reading so if I’m unable to sleep, a book invariable helps. I have a sea berth for each tack in the main saloon.

On my eleven day passage in 2018 from the Azores to Falmouth I averaged about 8 hours in 24 and arrived feeling quite normal.

Drinking and eating are important too but I find I’m less hungry underway. I remember feeling queasy halfway home from the Azores and I realised I’d forgotten to eat. A bowl of cereal, honey and banana settled my stomach. It was a reminder to look after myself, which requires discipline!

Remembering to eat. Azores to Falmouth 2018

Mike Richey would have strongly disapproved of me not drinking alcohol but I do drink gallons of tea. I did get nervous approaching Falmouth when I was down to my last fifty tea bags. Pete Goss always talked about making a brew if a decision had to be made!

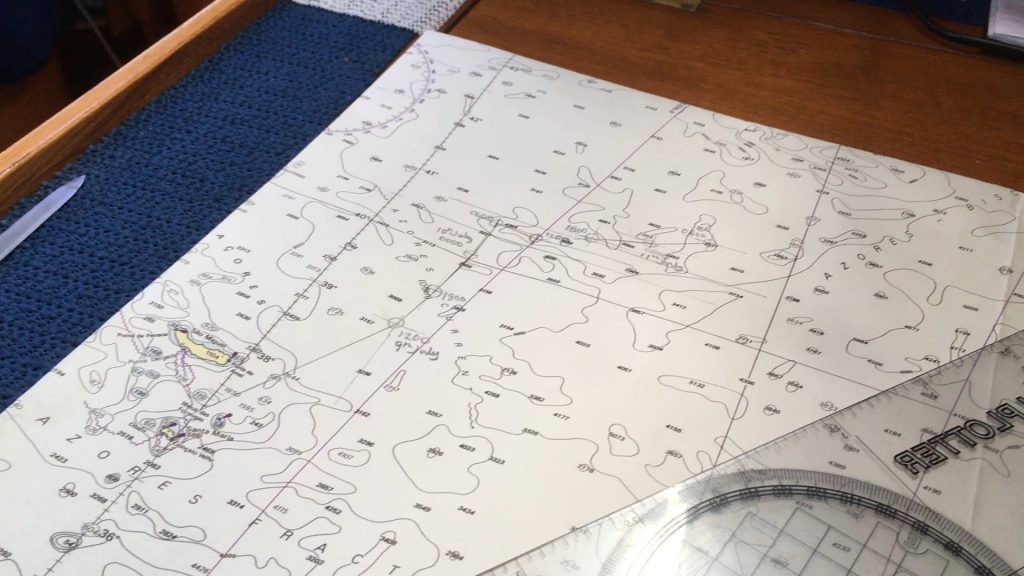

Another sailor described not having markers in his day when sailing offshore. I never experienced this and I found my routine helped enormously. I carry paper charts and compare my traditional navigation with the GPS. The position on the chart and log entries were made every six hours. Where do you start when all your electrics go down if you can’t remember what it said on the GPS before it went dead? By using traditional methods in tandem, you’re not going to go too far wrong. I also took noon sights.

I carry paper charts and compare my traditional navigation with the GPS

Noon Sights

I always reacted to the boat’s needs immediately. My main meals were morning and midday. I wrote a daily email diary to go with the ships log.

Unless conditions prevented it, I carried out my daily deck check looking for failures and chafe. Finding a small part of a split pin had me on my back scanning the rigging with binoculars. It worried me for the rest of the voyage. I showed it my friends at Evolution Rigging when I returned home but we were both none the wiser despite a microscopic rig check.

Daily deck checks looking for failures and chafe

A glorious day on passage Azores to Falmouth

I rarely slept the full twenty minutes, and I never felt I’d been fully asleep. But I found myself so completely in tune with the working of the ship that a slight change in the way she was working would have me straight up on deck and making the necessary adjustments. Slipping a reef in a sail could be practically done in my sleep.

I never felt lonely or bored offshore. I’m with my boat and she speaks to me all day. I’ve been much more lonely on land than I’ve ever been at sea. It would be easy to become a prisoner to idleness, so reacting to the boat’s needs immediately, and following a routine, avoids this.

I was always busy. Crossing Biscay was straight forward with fairly strong north westerly winds.

Crossing Biscay

14th June 2018 Cedeira North West Spain. A beautiful anchorage

For the 800 mile sail to Madeira from North West Spain I enjoyed the Portuguese Trades.

For sixty hours of that five day cruise I set the boat up and just watched, transfixed by the ocean as ‘Talisker 1’ ate 180 + miles a day. With a double reefed, and sometimes a triple reefed, mainsail on a preventer and a poled out handkerchief of rolled genoa we charged towards Madeira.

June 2018 bound for Madeira in the Portuguese Trades

For 60 hours never less than a F5, for the most part a F6 and sometimes a F7

Hardly a drop of water entered the cockpit. Never less than a F5, for the most part a F6 and sometimes a F7, I hardly altered course nor touched the sails. The steering system performed superbly. There was a day of blue sky and the ocean sparkled a brilliant fluorescent blue as the waves came up behind us like an unstoppable cavalry charge with foaming white plumes. The following day it was overcast and the sea became a forbidding malevolent slate grey. Another day a different world! The Trade winds can be very powerful.

In contrast, the 2,000 mile return home from Madeira via the Azores was upwind and had to be sailed. It was a lot of work to keep the boat sailing comfortably. By looking after myself properly I was able to sail the boat constantly. Look after her and she will look after me. I am the weakest link.

Sunset on passage ‘up wind’ Madeira to the Azores

Arrival Santa Maria, Azores from Madeira

Santa Maria

I realised how utterly insignificant and irrelevant my little ship and I were in the Atlantic. The ocean has no good nor bad intentions. It simply does not notice you’re there.

Doc also told me about the possibility of being mentally disturbed by the solitude and that in mid ocean sense and reason could leave you. I did hear voices and indeed singing. Church choir music. I often dreamt that someone came down the companionway while I was asleep. But I never felt alarmed by it. I felt amused more than anything else.

I was so keen to sail the boat, and only motored on my return from the Atlantic when leaving Falmouth for Dartmouth, and later from Eastbourne to Ramsgate in a mirror calm to get ahead of very strong winds.

I was always quite scared before departure. But once underway I felt I was in a world I understood. It is so easy to stay, as ‘harbour inertia’ sets in. Then finally, fully provisioned, you have to stand up and go.

‘Talisker 1’ Santa Maria, Azores

Vila Do Porto, Santa Maria, Azores

Me n ‘Talisker 1’ leaving Santa Maria bound for Falmouth

Anxious time. Last sight of Santa Maria, Azores as we depart for Falmouth. The voyage would take eleven days

I have a departure check list. I don’t want to be the one to round the headland, get swept by a wave and find my berth or the galley soaked just because I’ve left a porthole open. Simple checks include going through the grab bag and making sure the survival suit is close to hand.

I make a huge one pan dish before departure and then put the contents in one meal containers. There was enough electricity to run a fridge so the ready meals were there for the first six days of a cruise. I provision vast amounts of cereal, dried fruit, nuts, biscuits, cereal bars, tins of just about everything, rice, pasta, long life milk etc. Even without the fresh food also on board, I had enough food for months.

Sometimes I had to be prepared on departure for a long period of intense concentration with no sleep. I know I can function for up to 30 hours with no sleep. Leaving Cedeira, a few miles east of Al Coruna in North West Spain, I knew it would take 30 hours to be clear of land and traffic as we headed out into the ocean, crossing the very busy TSS’s off Cape Finisterre. A single-handed sailor cannot sleep close to land and traffic. Sea room is everything.

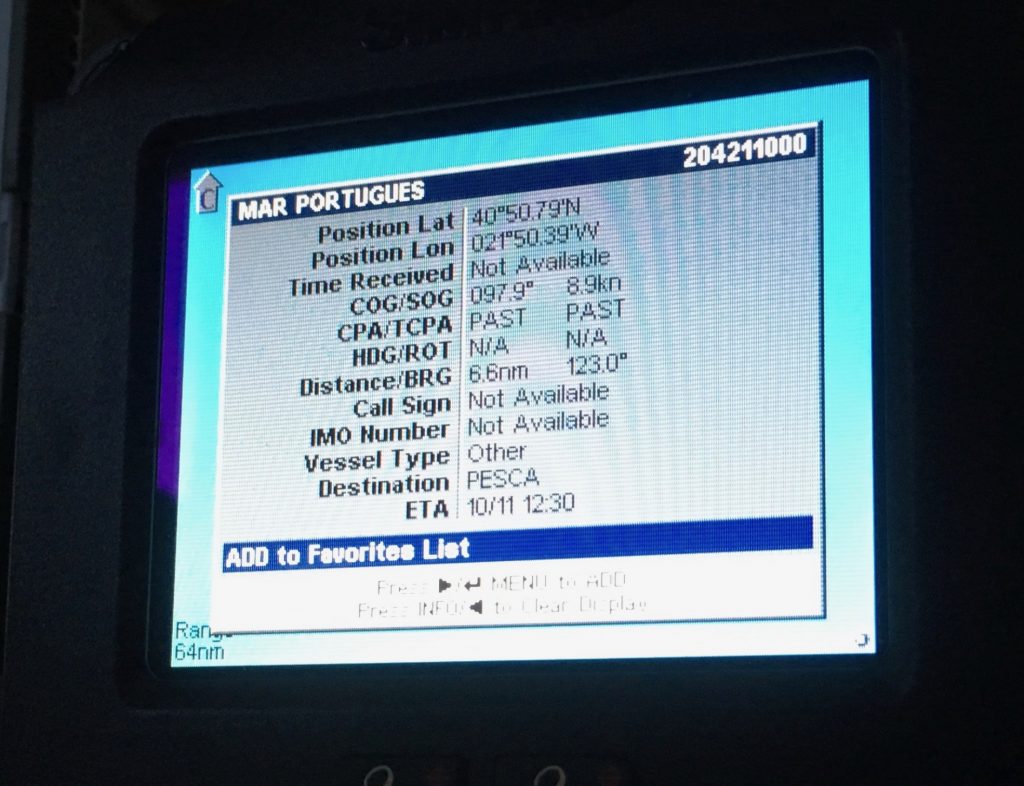

The Quantum Raymarine Radar and Simrad A150 AIS worked very well. An audible alarm was set on both Radar and AIS to guard the ship and on the very few times the alarm(s) sounded for traffic, I was alerted, and also woken immediately if sleeping.

AIS

Radar showing a squall

Squalls were frequent sailing home from Madeira

Radar picked up weather and this was helpful on dark nights. There were frequent squalls on the return voyage from Madeira via the Azores to Falmouth … all picked up on radar.

The solar panels performed better in Norwegian latitudes with nearly 24 hours of daylight, than in the much shorter days further south. In the Atlantic I occasionally ran the engine in the early hours to give the battery bank a boost. That was more precautionary than absolutely necessary.

I left each port with a full diesel tank of 136 litres. I carried a further 100 litres of fuel in 10 litre cans. The water tank was always full on departure with 200 litres. I carried a further 50 litres of water in jerry cans as well as the many half full bottles of water in the grab bag. I used water sparingly except when it came to drinking. Baby wipes sufficed for washing myself.

One of my favourite instruments was Iridium GO PredictWind. To easily download grib maps up to four times a day made me feel like I was cheating. Approaching Madeira we turned west to stay in the wind. A direct course to Madeira and we would have been in a flat calm. It was hugely helpful in the unusual conditions from the Azores to Falmouth, which was, for a thousand miles, a windward passage. It allowed me to plot my route across the ocean and stay in the wind. I did not use the inbuilt route planner.

I hardly used the satellite phone, which was my iPhone connected through Iridium GO. I was able to send daily emails to family and friends. The whole thing worked flawlessly.

I have to thank marvellous Marleen Cleyndert and the rest of the team at PredictWind in New Zealand for their patience and high skill in helping me understand how it all worked. Marleen has twice sailed round the world and most of the team are sailors. Nice to know that the people helping you are sailors too and understand what you’re going through!

I will not leave without a good weather window for at least the first 48 hours if the voyage is of some length. If a system or part of the boat is defective or broken before departure I have to be pretty certain that the passage can be completed without it creating an adventure!

Doc and his ship were hit by a serious lightning strike in South America. As well as being injured himself, the boat needed almost a total rewire. Doc carried out all the work himself, incredibly from his own on board spares. Many parts ordered failed to arrive. Once happy that he and his boat were in a fit state, Doc and ‘Tuesday’ curtailed sailing further south and returned home safely via St Helena and the Azores. It says much for his preparation that he carried so many tools and spares, and knew how to use them.

I have to know how things work. As an example, I am grateful that Mark, at Suffolk Marine Safety, invites me over to see the process when he is about to service my life raft. I guess many of us, despite attending a sea survival course, have no idea what to expect of their life raft until the unthinkable happens.

I don’t seem to have dramas with other ships, though once returning from the Azores a vessel steadily approached from our port quarter. The CPA was less than half a mile. Winds were fairly light and the ocean was resting, gently undulating like a sleeping giant taking her deep breaths. Slowly the vessel, making about 12 knots, got closer, drew level and passed a half mile in front. My calls had gone unanswered. A check with binoculars showed the bridge to be empty. The fishermen were probably all below, playing Monopoly.

The very few other ships I encountered did acknowledged my VHF call. In even moderate conditions the CPA could swing from 0 to 1 mile. On their more stable bridge with their superior instruments, watch officers were able to tell me they were passing well clear or that they had altered course a couple of degrees. One watch officer wanted a long chat. Where had I been? What were my plans? I think the watch officers welcome the distraction when well offshore. Another large fishing boat returning to Portugal from the Grand Banks actually altered course to come and see us. The captain, himself the owner of a Dufour that he raced at home, was kind enough to tell me how well balanced ‘Talisker 1’ looked as we smashed our way to windward under double reefed main and stay sail. Nice!

A large fishing vessel heading home to Portugal from the Grand Banks and a lovely VHF conversation with her Captain

The secret is to react very early. If there is no response from a ship, sail as quickly as possible away from danger.

I always wore a PLB on my belt.

Madeira to the Azores. My PLB on my belt

I often go through the ‘what ifs?’ I try to have thought through or practised a plan of action for most scenarios, and also to remind myself where everything is located on the boat. However, something could happen that is unforeseen and therefore the ability to improvise is essential. If you’re surprised by something at sea you probably should not be out there.

Experience avoids panic. What starts as minor problem can become a major one, so nipping it in the bud is important. There is loads of time if you’ve practised and know what to do. Never make the same mistake twice, nor a mistake you’ve read about.

When I arrived in Falmouth from the Azores I felt I could have sailed on indefinitely. I did enjoy arriving, as a daughter, a son-in-law and two small grandsons were in Cornwall. Nonetheless I felt my routine could have survived for a much longer distance.

Approaching Lands End. Have the Royal Navy come to meet me?

St Mawes Cornwall. ‘Talisker 1’ proudly flies the courtesy flags of France, Spain, Portugal, Madeira and the Azores.

I would not have sailed into the Atlantic in 2018 if there had not been a week of strong easterlies at the beginning of June to get me down Channel. It was one of a few cruises planned. If the winds had been westerly I would have headed north with the hope of an assault on Faroe or even Iceland. I also want to sail to Arctic Norway.

Looking back I now feel like it was someone I knew very well who’d sailed the 4,000 miles in two months in 2018.

Would I do an ocean passage again? Hell yes! It’s what I do! If there were no family at home and a growing number of grandchildren, I would be a permanent boat gypsy.

My working life was not unduly interesting and my desire to sail further occupied my mind a great deal. I made the time to train properly. So perhaps I should not be surprised that people who have less time to prepare seem to have more ‘adventures’ than I do!

The docks of Felixstowe on our return from the Atlantic July 2018

Our return to the River Ore and our home port of Orford. Doc and his Orford 10 Footer came down river to welcome us home …

Our 2018 4,000 mile voyage

Thnks for taking the time to describe your preparations and experiences. I would like to do something similar, altho starting from Portimao!

Great post, James. Thanks for sharing!!

And thanks for the plug!

My sailing heroes! Thank you for reading the post x

As a non sailor l am speechless. I did that route on a cruise and couldn’t stay upright across Biscay. You’ve grown up a lot since the days l knew you. Amazing achievement and many more to come by the sounds of it.

Well done

Hi James, could have written it myself, fully agree with all your preparations and thoughts.

Did a round trip to the Azores (Horta) myself in 2017 and I’m longing to do it again. I have to work 1 year before retirement. In 2022 we plan to go to the Baltic for 3-4 months after that it will probably be solo to the Algarve, maybe Madeira, maybe Canary’s, but definitely back via the Azores.

Maybe we’ll meet somewhere in the coming years! Stay safe and prepare for the worst, enjoy the best!

Hi Rob. What strange times we are having. Thank you for reading my post. Yachting Monthly ran it in the December issue but it was sadly but understandably shortened. Your voyage to Horta sounded amazing. I’m not sure I’d revisit the Canaries. I’d love to return to Porto Santo, Madeira and do more islands in the Azores. I did love Santa Maria. I’m always trying to find ways of getting away and back home, with my boat, in a summer. Ipswich, Madeira, Azores and home was ideal over a two month period. Last year I’d hoped to sail towards Faroe and possibly Iceland but … it was not a time to leave home waters. This year is not looking promising. I launch in a few days and will enjoy the Thames Estuary. Yes please to a meet up. If your ever on the east coast of the UK around Ipswich please remember me. ATB James